Reducing antibiotic use in food animals

- D-USYS

- Institute of Integrative Biology

As the world is growing ever more hungry for meat, the routine use of antibiotics in food production is becoming of considerable concern. A team led by Thomas Van Boeckel, researcher at the Institute of Integrative Biology (IBZ) at ETH Zurich, conducted the first global assessment of different intervention policies that could help limit the projected increase of antimicrobial use in food animals.

USYS-News: Antibiotics in food animals are often used as growth-promoters or as surrogates for poor hygiene measures. What is the biggest concern about them – now and, say, in 2030?

The concern will remain the same in 2030: the untargeted use of antibiotics in animals provides the ideal breeding ground for bacteria to evolve resistance. At some point, resistance levels to common drugs are going to be so high that treatment will not work anymore and this could lead to more frequent epidemics and major disruptions in food supply. So in brief, overusing antibiotics could have serious consequences for humans but is also not in the long-term interest of the animal industry.

What did you find about the consumption of antibiotics on a global level?

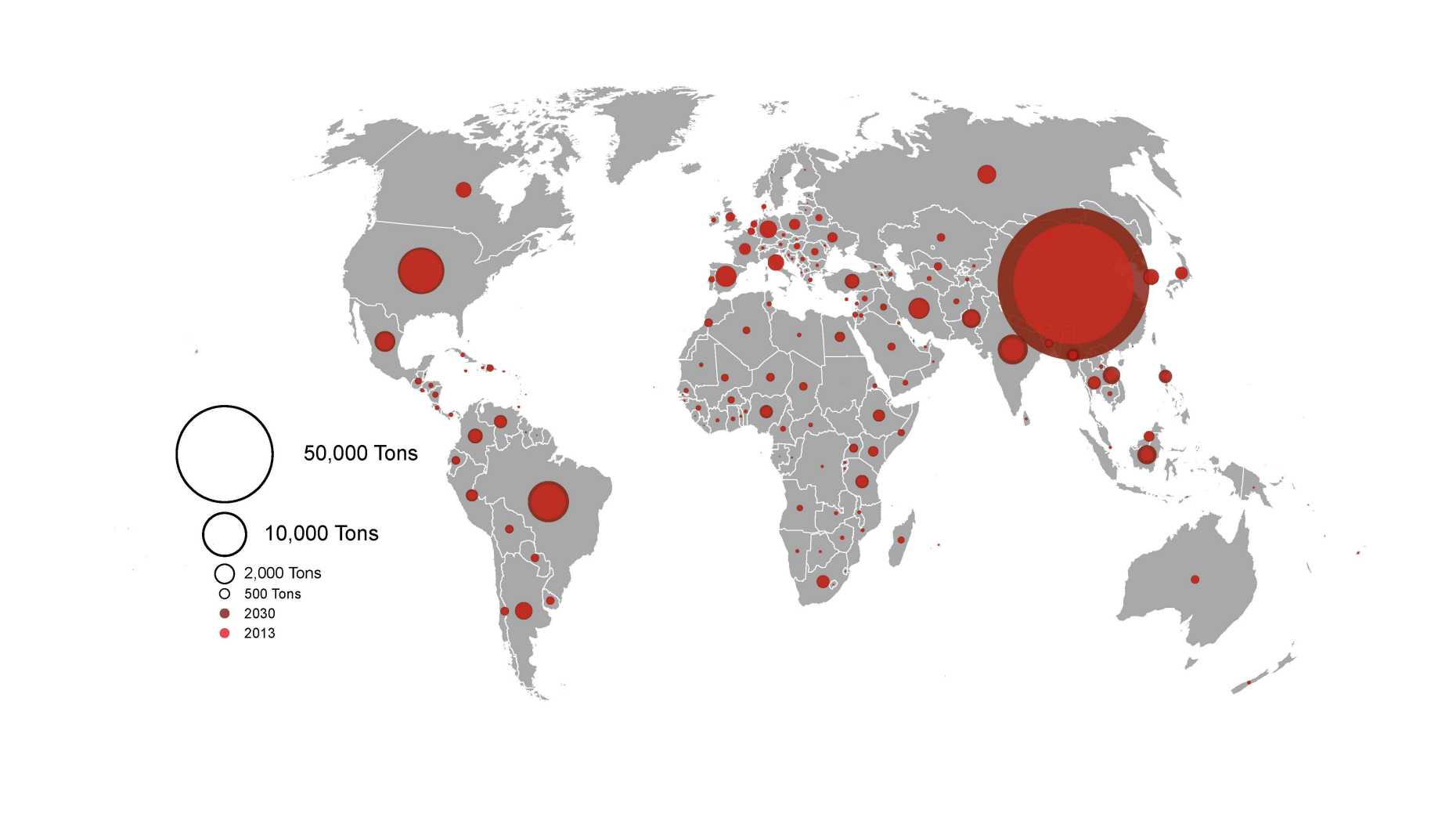

The study external page Reducing antimicrobial use in food animals, published today in Science, found that worldwide consumption of antibiotics is expected to rise by a staggering 52% percent and reach 200,000 tonnes in 2030 barring any actions. This is an alarming upward revision from already external page pessimistic estimates made in 2010. This notable increase is due to recent reports of very high antimicrobial use in animals in China, and other fast growing economies.

What measures do you suggest would be the most effective to reduce antimicrobial use in animals?

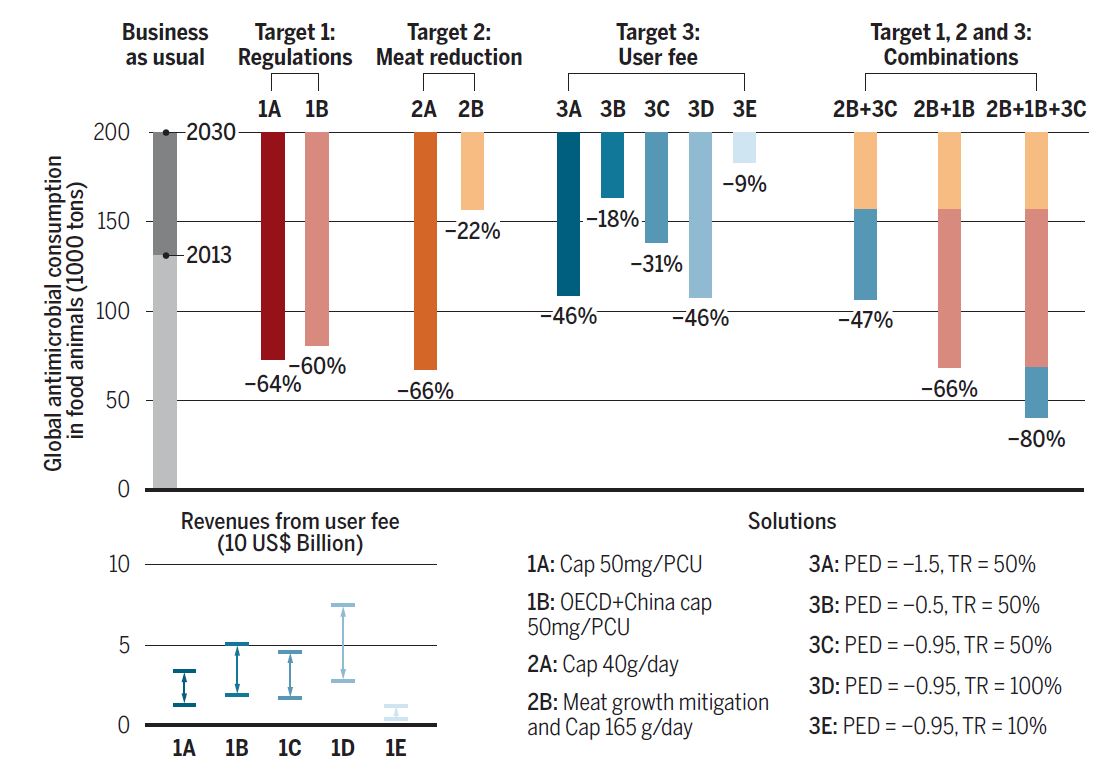

If we were to reduce antimicrobial use we need to either eat less meat, adopt strict regulations or tax non-human antimicrobial use. These policies are not mutually exclusive, and we estimated that the effect of combined interventions could reduce the global consumption by up to 80%.

What does that mean in concrete terms?

Our main finding is that we could actually achieve a meaningful reduction – about one third – of the projected current global consumption if we tax veterinary antibiotics. Using a tax would also generate a substantial amount of money – around two billion that could be reinvested in drug development or used to subsidize improvement in hygiene measures on farms. Another possibility is stricter regulations in the form of limit values.

Overall, we think that the stricter rules for limiting antibiotics in livestock farming would be very effective, but this would probably be logistically harder to enforce than simply taxing antibiotics when they come out of the factory.

Let's take a closer look at the figures: Compared to a business as usual scenario, a global regulation putting a cap of 50 mg of antibiotics per kilogram of animal per year in OECD countries could reduce global consumption by 60% without affecting livestock-related economic development in low-income countries. However such a policy may be challenging to enforce in resource-limited settings. An alternative solution could be to impose a user fee of 50% of the current price on veterinary antibiotics: this could reduce global consumption by 31% and generate yearly revenues of between US$ 1.7 and 4.6 billion.

What methods did you use and what were your restrictions?

We used multivariate regression models to predict antimicrobial consumption, in combination with basic microeconomics tools to evaluate the effect of an ad-valorem tax on antibiotics. The main limitation was the access to harmonized data on antimicrobial sales and prices. Currently, only 38 countries report such information, and the animal health industry unfortunately declined to contribute additional data to help improve our estimates.